By Pooja Balasubramanian /

Four years after the Bretton Woods Conference in 1944, the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights stated that “[e]veryone, as a member of society, has the right to social security.” Social security or social protection until today is understood as a mix of different tools like insurance and social assistance in the form of cash, in-kind transfers (food or other materials) and employment guarantee schemes. Despite normative frameworks of a rights-based universal social protection system, endorsed by the International Labour Organization’s (ILO) Convention of Social Security or initiatives such as the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable development and the World Bank and ILO’s Global Partnership for Universal Social Protection 2030 (UPS2030), the reality is far from this.

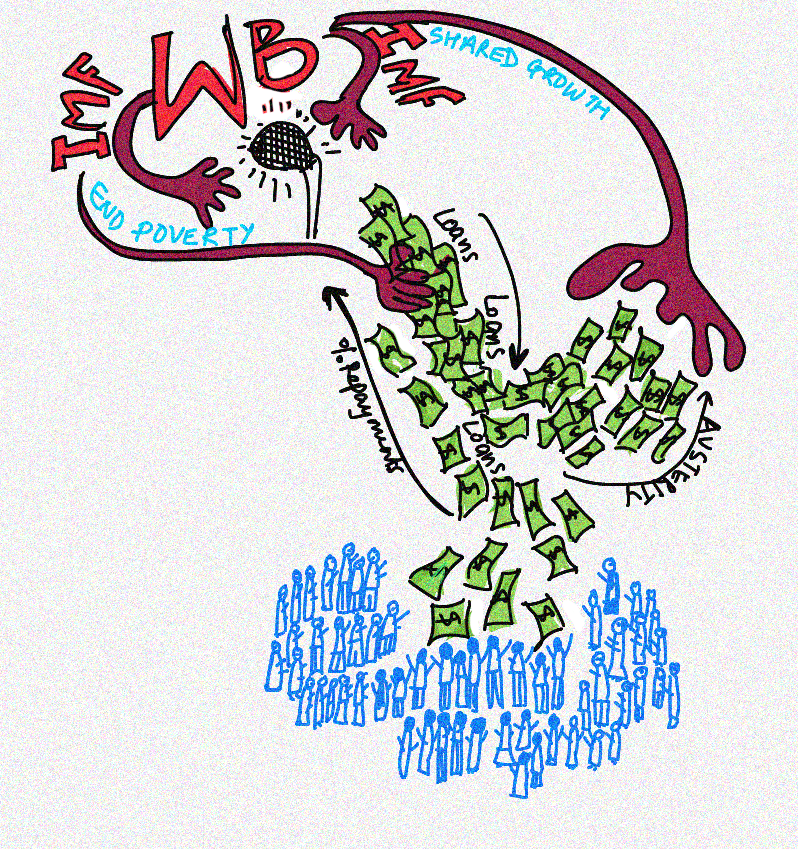

Before the pandemic, in 2019, more than half of the world’s population was left with no, or only partial, coverage of social protection programs. The gap between commitment and reality was especially pronounced in low- and middle-income countries, with only 29% of the global population covered by the full range of comprehensive social benefits, from child and family benefits to old-age pensions. The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF), also known as the Bretton Woods institutions (BWIs), need to be held responsible for these abysmal statistics, especially because they are providing up to two thirds of global aid for social protection.

The tools are there to create a rights-based social protection system. It is possible to de-commodify[1] social services based on the local context through redistributive policies and economic sovereignty of countries. Therefore the inertia and abject lethargy from the BWIs and rich donor countries seems increasingly deliberate.

This suspicion begins to gain more truth when we see how BWIs (along with the rich donor countries) have not only interfered with economic decisions but have also made sure that the financing and implementation of social protection schemes follow a Eurocentric perspective along with a continuation of colonial legacies.

In complete disregard of the context and sovereignty of the local people today, in most countries of the Global South there is a forced acceptance of the World Bank’s understanding of social protection. Namely, it is a “safety net tool” or a “risk management strategy” for poverty reduction, with a new buzzword of ”graduating” the poor out of poverty making the rounds. All of these terms promote the idea that social protection and access to social services are temporary and a transient need rather than a long-term system centred on shared rights.

Why it is difficult for countries to implement their own rights-based social protection system?

A short answer to this is the immense economic control of the Bretton Woods institutions (and their most powerful funders) on how countries can tackle their development strategy. By wielding their positions as lenders, the BWIs have repeatedly imposed austerity measures preventing countries from investing in long-term structures and systems of social protection.

The consequence was clear during the COVID-19 pandemic: amid massive disruptions and loss of lives, particularly of people at the frontlines of the crisis. With no system of social protection, countries resorted to short term and limited social protection policies that lasted on average for only 3.3 months.

The response was similar during the economic crisis of 2008-09, when spending on social protection increased only in the first year, followed by strict policies of budget cuts and reduction in public spending on social protection across low and low-middle income countries.

Despite a detailed report by the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) on the drastic negative consequences of austerity and low public spending for public services, 72 low- and middle-income countries implemented budget cuts in 2010. As of 2020, the list has increased to 84 countries. In all of the 124 loan conditionality evaluated between 2016 and 2021, austerity and cutting down public expenditures was the main policy tool of the IMF.

For low- and middle-income countries, the World Bank and IMF continue to shape the rules of social protection spending (including health and education) in exchange for concessional loans. For instance, the IMF introduced a minimum spending floor for social protection in their lending programs so as to ensure a minimum effort towards social services in cases of cuts. However, these spending floors were rarely met. In West Africa, only 46% of the social protection floors were implemented, one of the regions with the poorest implementation of the social protection floors across the continent. Between 1994 and 2015, Benin met only 34% of its priority spending floor and had to specifically cut spending on poverty reduction policies to meet other fiscal austerity objectives of the IMF.

Two immediate consequences of austerity that have also impeded countries from creating rights-based social protection systems are: a) the failure of so-called targeted social protection schemes, and b) the onslaught of direct privatisation and financialisation.

A) The failures of targeted social protection

The latest report of the UPS2030 led by World Bank and ILO discuss the implementation of universal social protection “[t]hat is available and accessible to all whenever and wherever they need it”. One might think that this is a good step in the direction of achieving a rights-based social system. However, in reality, the World Bank continues funding and promoting targeted programs that is diametrically opposite to universalising social protection. A Human Rights Watch report as recent as August 2021 and other World Bank reports reveal targeted social protection programs continue to be prioritised and funded by the World Bank.

Targeting, as the word suggests, means selecting a certain population group that is extremely poor and only give them access to social protection. The groups are selected by using one or a combination of factors, namely, location, age, ethnicity, community and income.

The proxy means test (PMT), which is a proxy for an income-based targeting method, is widely used and promoted by the World Bank across their programs. Its use is based on the assumption that in many low- and middle-income countries, it is expensive to collect accurate information on household incomes. The PMT method tries to predict a household’s welfare based on observable factors that might correlate with household income such as access to water and sanitation, housing quality, education levels, among others. Despite evidence that using such targeting practices leads to exclusion of many vulnerable and minority groups, the World Bank and other international development agencies continue to use and endorse PMT by claiming that it is a cost-effective way of delivering social protection.

An internal review of the IMF in 2019 found that in 64% of the cases, the Fund had approved recommendations introducing or expanding targeted social protection while in 18% of the cases, they recommend downsizing programs that are not targeted. Kyrgyzstan and Mongolia are examples of two countries that lost the opportunity in the last 10 years to create a sustainable rights-based child benefits program due to the push from the IMF to target their child benefit policy as part of the IMF loan conditionality.

Exclusion due to PMT targeting of social protection has shifted all the risk onto the individual. It created a “missing middle” where, for instance, those who are in informal, poorly paid work do not fit the conditions of the targeted policy either because they are “above” the target, fluctuate into being below and above “extreme poverty,” or were wrongly categorised. While the excluded groups vary across country contexts, the disabled, women, elderly women and children have borne the heaviest consequences of such targeting.

A 2017 study by Kidd, Gelders & Bailey-Athias compared the universal old-age pension scheme in Georgia (no targeting) with South Africa’s child support grants that used a means test to target the poor based on reported income of the caregiver, and the Philippines’ Pantawid scheme that used a PMT method. The authors found the universal scheme for pensions to be the most effective in reaching the poorest (100% coverage amongst the lowest income decile). This was onlyfollowed by the child support grants with minimal exclusion, and lastly, the Pantawid scheme in the Philippines as the least effective despite targeting the extreme poor (55% coverage of the extreme poor).

In some cases, these targeted programs are short term, in the form of pilot programs for limited geographical areas, lacking a stable legal and financial foundation. These programs have ended up becoming experiments on the poor.

B) Privatisation and financialisation

Another consequence of austerity policies and loan conditions by the BWIs and lender countries has been retrenchment of the public sector from taking responsibility for social goods such as healthcare and education, and instead promoting the private sector to ‘invest’ in them.

As of August 2023, the IMF has 38 lending arrangements with 27 African countries that enforces a reduction in public sector wage bills and the ”restructuring” of public sectors such as health and education. There has also been a tendency to homogenise the broad nature of social protection into one instrument, namely cash transfers, and outsource the distribution system of cash transfers to private fintech, or financial technology, companies.

Along with a push for the privatisation of social services, the World Bank and other development institutions have been promoting the financial sector as a key agent for raising household incomes of the poor. This is under the guise of financial inclusion, or as they call it, “banking the unbanked.” In the last ten years, five of the largest development banks committed close to USD15 billion towards microfinance institutions as a tool for poverty alleviation despite extremely weak evidence on any transformative roles of microfinance. In many cases, national governments have also been actively strengthening the private sector and microfinance institutions while decreasing the government’s contribution to creating long term social protection.

The inaction of the state and the takeover of social protection by profit-seeking entities looks different across different continents. In some cases, the neoliberal state has played the role of the enabler by outsourcing the process of transferring the minimal cash transfers to private multinational companies (MNCs) in South Africa, or bundling cash transfers with financial services through private banks in Brazil. These processes have given private companies and banks access to peoples’ data, who eventually use the data to lend microcredit to the same beneficiaries and often retain their cash transfer as collateral. In Nigeria, due to the extremely low public investment in healthcare, the private sector took over this space and provided healthcare at very high prices with very low levels of coverage (mostly concentrated in urban cities).

In other cases, the state has been providing a thin layer of safety net sinadequate to fulfil basic needs, with people turning to either private insurance companies, microfinance institutions, or moneylenders for short term survival loans. In the case of Vietnam, Cambodia or India, the cash transfers, social insurance, and health insurance subsidies provided by the state have been insufficient to cover the high private healthcare costs, paving the way for predatory private life insurance companies or microfinance institutions.

The lack of an adequate social protection system has become a hotbed for such private corporations and lenders (both microfinance and moneylenders), increasing the indebtedness amongst the rural poor

How can we achieve a rights-based social protection? Policy recommendations

A rights-based approach to social protection should put social justice, equity and dignity at the centre of any society. Such a social protection system requires retaining the sovereignty of the people. It could have components such as:

A) National and international legal mandates for a rights-based social protection

A rights-based social protection system needs to be backed by a legal framework, anchored within a country’s constitution, guaranteeing the right to access social services. In addition to national legislation, an international legal framework such as the ILO Social Security Convention, 2002 (No. 102) is necessary to guarantee rights of the people, especially when they are faced with external pressures or violent conditionality imposed by institutions like the IMF and World Bank.

Of course, legal frameworks do not directly translate into effective coverage and adequate benefits, especially when confronted with neoliberal governments. For example, India’s National Food Security Act (2013), that came into legislation after sustained efforts and mobilisation, guaranteed legal rights for 75% of the rural population and 50% of urban population to receive adequate quantity and quality of food. The current Modi government has found ways to undermine the Act by defunding related social programs like school feeding and maternity benefits, as well as by using outdated census information for the list of priority households under this Act.

Nevertheless, establishing entitlements in national legislation can assist civil society groups and social movements to mobilise, confront their governments, and hold states accountable to do more in extending and creating stable social protection systems. Legal entitlements give people’s movements and their allies an opportunity to defend their rights, hold the government responsible to the needs of the population, as well as legitimacy in the public view, as ways of overcoming various harmful social norms.

At the national level, Thailand has been an important country case that has progressively developed a legal framework to ensure the right to social security for all. Ever since the implementation of the Social Security Act in 1990, Thailand has brought schemes for maternity and child care, old-age pension, disability, healthcare and unemployment under a series of regulations within this Act. As a complement to the Social Security Act of 1990, Thailand’s legal social protection framework includes a National Health Security Act (2002) that guarantees a tax-based health coverage scheme to include 76% of the population uninsured by other existing schemes.

At the global level, as of 2002, 66 member states have ratified the ILO convention on social security, mostly from high or high-middle income countries.

B) Alternative financing for social protection

Lending programs imposed on countries, on the pretext of economic prosperity and development, have in reality pushed them into more debt. To solve this indebtedness, the BWIs have come up with a genius solution – of offering more debt. Ghana, for instance, is on its 17th deal with the IMF, and as of 2023 classified as a debt-distressed country with public external debt at 42.4% of its GDP. The country’s education expenditure has been cut by 75%. Drastic reductions in social spending has caused a shortage of meal programmes that fed 3.5 million children in public schools.

According to the Debt Service Watch report, out of the total revenue earned by countries, more than half is going into debt repayments (or debt servicing): 57.5% for low-income countries and 45% for low- and middle-income countries. More importantly, debt service is exceeding 50% of the combined expenditure on health, education, social protection and climate only in Africa, taking away from urgent spending to confront social and environmental crises.

For sovereign countries to be free from the current economic slavery of the BWIs, a first step is for the “debt-distressed” countries to come together and implore the BWIs to cancel all of the debt, particularly debt that is hampering a country’s ability to provide basic public services and take necessary climate action.

The second step is punitive action against the BWIs for perpetuating violence on the majority of people in the world – a violence and economic occupation that has lasted for 80 years now.

The third step is for sovereign countries to implement real progressive taxation in the form of wealth, corporate taxes and taxes on the financial sector. This also means halting implementation of regressive taxes in the form of value-added taxes (VAT) that only has a detrimental impact on women in general, older women in particular, and children. There are many ways to do this. The reforms suggested by the Independent Commission for the Reform of International Corporate Taxation proposed a minimum effective corporate tax at 25% worldwide, to stop profit-shifting and prevent countries from engaging in a “race-to-the-bottom”. Another option include taxes on the financial sector, or Financial Transaction Taxes (FTT), levied on various financial instruments such as shares, bonds, derivatives. An FTT is easier to implement as it can be monitored using technological advancements, making tax collection efficient, and generate substantial revenues. Additionally, FTT can play an important role in discouraging short-term financial speculation which poses high risks to economies.

C) De-commodification of healthcare and education, and universal social protection

Public services provide equality of opportunity through a common set of services available to all, irrespective of one’s income. Universal social protection means that all people who face a similar risk are to receive the same kind of support, and need should determine the extent of this support. Social protection today is restricted to narrowly targeted cash transfers and insurance schemes, and the ownership of essential basic services is in the hands of private financial sector. This has contributed to both exclusion from access and also general inability to afford basic necessities. In order to create a just and rights-based system a full-de-commodification of social services is needed. This also means that cash transfers alone are not enough and it has to be complemented with in-kind transfers and publicly-provided social services.

In order to reverse the trend of privatisation and financialisation, and reclaim the social protection systems from a rights-based lens, we need a) a creative mix of universal cash transfers and in-kind transfers and b) de-commodification through public provision of social services such as healthcare and education for all. This recommendation acknowledges that both cash transfers and in-kind transfers can be truly universal only if it is combined with public provision of social goods like healthcare and education to achieve justice and eliminate inequalities. In this way, a comprehensive social protection system ensures both the means (cash and in-kind transfers) as well as access to quality services for all. At its root is the need to promote equality, opportunity and social justice, as necessary conditions for universal human rights-based social protection.

Pooja Balasubramanian is a feminist social economist currently working as a postdoctoral researcher at the German Institue of Development and Sustainability (IDOS). She is interested in questions concerning the politics of poverty, inequality and debt, and financialization of social reproduction and care.

[1] De-commodification is a political economy concept that is defined as the strength of social entitlements and citizen’s degree of immunization from market dependency